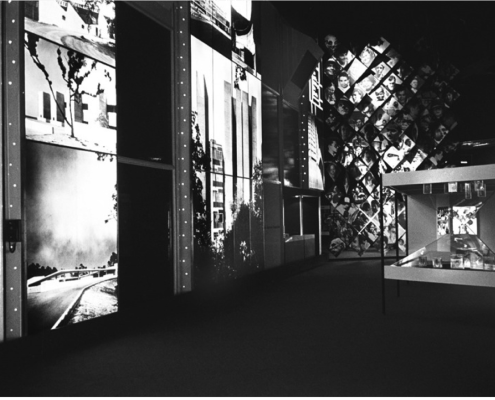

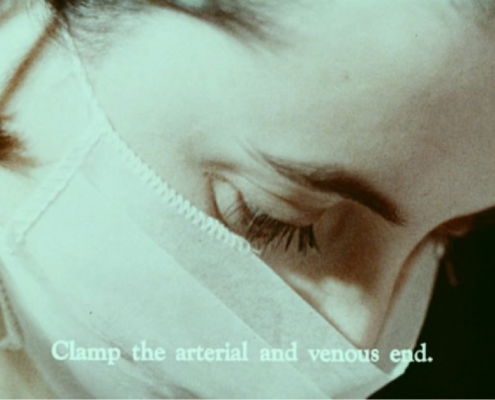

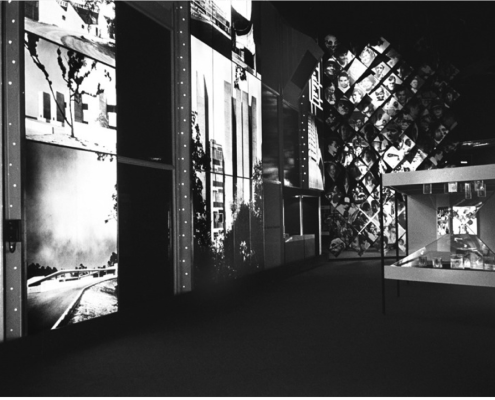

After its provocative opening sequence – the first graphic depiction of a live birth on film ever seen by a general public mass audience – director Robert Cordier’s film followed six cutting-edge medical procedures in Montreal-area hospitals that loosely suggested the cycle of life from birth to death. The film was the centerpiece of the Meditheatre, a hexagonal stage and screen chamber with spiral viewing gallery at the core of the Man and His Health pavilion. The film used experimental and surrealist techniques from the French new wave and the new American documentary cinema, and was graced by a deft editing rhythm years ahead of its time. The combined content and cinematic novelty had a dizzying effect and the film itself became a medical event, with an average of 200 viewers a day fainting. It was accompanied by a stilted, often highly technical and didactic narration track that was occasionally handed off to a troupe of six actors on a series of hexagonal stages rigged out with state-of-the-art hospital equipment. Part re-enactment, part chorus, part dumb show, the theatre component gave the film a live feel. Three sequences offered close-ups of invasive procedures including a Caesarian section, open-heart surgery and the insertion of stereotactic stimulation needles into the brain of a Parkinson’s patient. Two others were portraits of sufferers: a kidney patient on a dialysis ward and a child thalidomide victim without arms being introduced to a robotic arm prosthesis. The other sequence depicted an experimental nuclear medicine apparatus for mapping lung function with xenon gas. The film explores a number of themes like the inseparability of humans and machines in modern medicine, the circulation of blood in a variety of apparatuses, the overlap between medical representation and high and popular art, medical masks, and the human hand.

-Steven Palmer

Robert Cordier

Robert Cordier was a Belgian-American poet, theatre director and stager of happenings who was working at the heart of the New York art scene when the pavilion’s interior designer, Peter Harnden, commissioned him to create a combined film and stage event for the Meditheatre. Influenced by surrealism, and particularly Antonin Artaud’s theatre of cruelty, from his formative years as an actor in Paris, Cordier had collaborated with a number of notable writers and artists from the era, including James Baldwin, Shel Silverstein, Alan Ginsberg, Salvador Dalí and Andy Warhol. A chance encounter led him to engage photographer and filmmaker, John Palmer (Ciao! Manhattan), who had been central in introducing cinema to the Warhol (he had a notable creative and technical role in the signature experimental piece, Empire). While Expo was up and running, Cordier was directing a landmark rock and roll television special, Murray the K in New York; his independent 1973 feature film, Injun Fender, a surreal portrait of the New York subculture, won festival prizes in Europe. The stage continued to be Cordier’s main focus, however. He returned to Paris in the early 1970s to dedicate himself to directing and translating plays, and to teaching, and he trained many of the leading actors and directors working today in French film, television and theatre (among them Emmanuelle Chaulet, Xavier Durringer and Eyé Haidara).

Deidi Von Schaewen

Deidi Von Schaewen – then a recent graduate of Berlin’s prestigious Hochschule for the Arts – worked on the pavilion’s graphic design elements and the showcases. She would go on to be a world-renowned photographer of formal and informal architecture.